The Mission of Equal Justice, Inc.:

To provide free or low-cost legal services to indigent people and marginalized communities, thereby increasing access to the courts and administrative agencies of the United States and promoting the integrity of the legal system and the rule of law.

Why?

It was never supposed to be like this. When the United States declared independence, most of the law citizens needed to know fit into the four volumes of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. There was no “law school”; lawyers trained as apprentices, much like carpenters or blacksmiths. The body of knowledge necessary to practice law wasn’t sufficient to warrant a doctorate degree until the 1900s. The law was simple enough that few people required representation, and lawyers worked for reasonable wages.

Immigration laws barely existed. While there were restrictions on citizenship as early as 1790, for the first century of the Republic, there were no effective restrictions on who could come to live and work in the United States. America was open to anyone with the courage to come.

Those days are long gone. Life is more complex. Hardworking people facing legal trouble are bewildered by a morass of local, state, federal, and administrative courts and regulatory agencies. While our lives are more interconnected with each other and the outside world than our forefathers could have imagined, who is able to come to America to live and work is ruled by arcane statutes and regulations. Navigating the system without an attorney is often more intimidating than it is worth, even for people with a modicum of education. Many simply give up or refuse to fight for their rights in the first place. Global trust in the rule of law is in decline.

Simultaneously, the market for legal services permits attorneys to charge fees almost as offensive as the conduct that brought people to court in the first place. “Justice” is available only to those who can afford it. Those that suffer most from lack of representation are the same as those that suffer first from other social problems: the poor, immigrants, and traditionally marginalized communities. It is a two-tiered system making it almost impossible to achieve the dream of our founders: a society where “all men are created equal” and where no government can “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

If the law cannot be applied equally, how far is the United States from the tyranny we’ve long claimed to despise? How long is it until the Courts designed to protect minority interests serve only those who can pay for the results they desire?

It stops here.

Equal Justice, Inc. (EJI) is a nonprofit founded by people who believe in American ideals, yet have seen it fall short of that vision with their own eyes. EJI steps in where the system fails: at the point where access to affordable legal representation means the difference between justice and abuse — fairness and exploitation. To be sure: it’s people helping people, but the implications are for more significant:

It’s about making the system accountable to those easiest to ignore so no one has to question its integrity when the bell tolls for us.

A Short History of Access to Justice

-

Canon law records indicate that lawyers were occasionally appointed to serve persons too poor to pay their fees, but the practice does not appear to have been widespread.

-

Parliament passed a law formally recognizing in forma pauperis status in all courts of record within England. The status permitted the indigent litigants to file cases without the payment of any court fees. The law also provided further that the Chancellor and Justices should assign attorneys to poor people and that the attorneys should give their counsels without taking any reward.

-

Criminal defendants were — for the first time — permitted to retain an attorney to contest the facts of the cases against them, rather than conducting their own defense. However, the courts did to provide an attorney for the accused, and the accused had to pay for his own lawyer.

-

The newly drafted Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution of the United States, guaranteed the right to counsel in criminal cases. The guarantees were in direct response to English failures to allow counsel to criminal defendants in Colonial America. However, neither Congress nor the States appropriated funds to pay for an accused person to have an attorney.

-

Most small claims for civil justice were pursued without lawyers in local informal tribunals, like justice of the peace courts or county courts. Anyone, including wives, minors, and slaves, could come under the jurisdiction of these courts, which were regulatory agencies and enforcers of local laws as well as dispute-settlers. Yet even in regular trial and appellate courts, the reports show many cases with lawyers litigating relatively small sums like $50 to $100. Entry barriers to the profession were almost nil in most states, so litigants could have the benefit of low-cost advice.

-

The First American legal aid organization opens in New York to help women workers collect fraudulently withheld wages.

-

Widespread workplace injuries in nascent industrial plants, mines, and railroads cause the development of personal-injury suits.

A specialized bar, mostly Jewish and night-school trained, developed to serve the injured and their families. They took a contingent fee: 30 to 40 percent of any damages recovered, nothing if they lost.

In response, elite lawyers representing business interests tried to close down the night schools and promulgated bar-association bylaws targeting contingency fees.

-

The Legal Aid Society opened in New York City to aid newly arrived Jewish immigrants.

-

The Chicago Protective Agency for Women and Children expands to include a paid staff handling over four thousand cases including wage claims and victims of domestic violence, who were often ignored by courts.

-

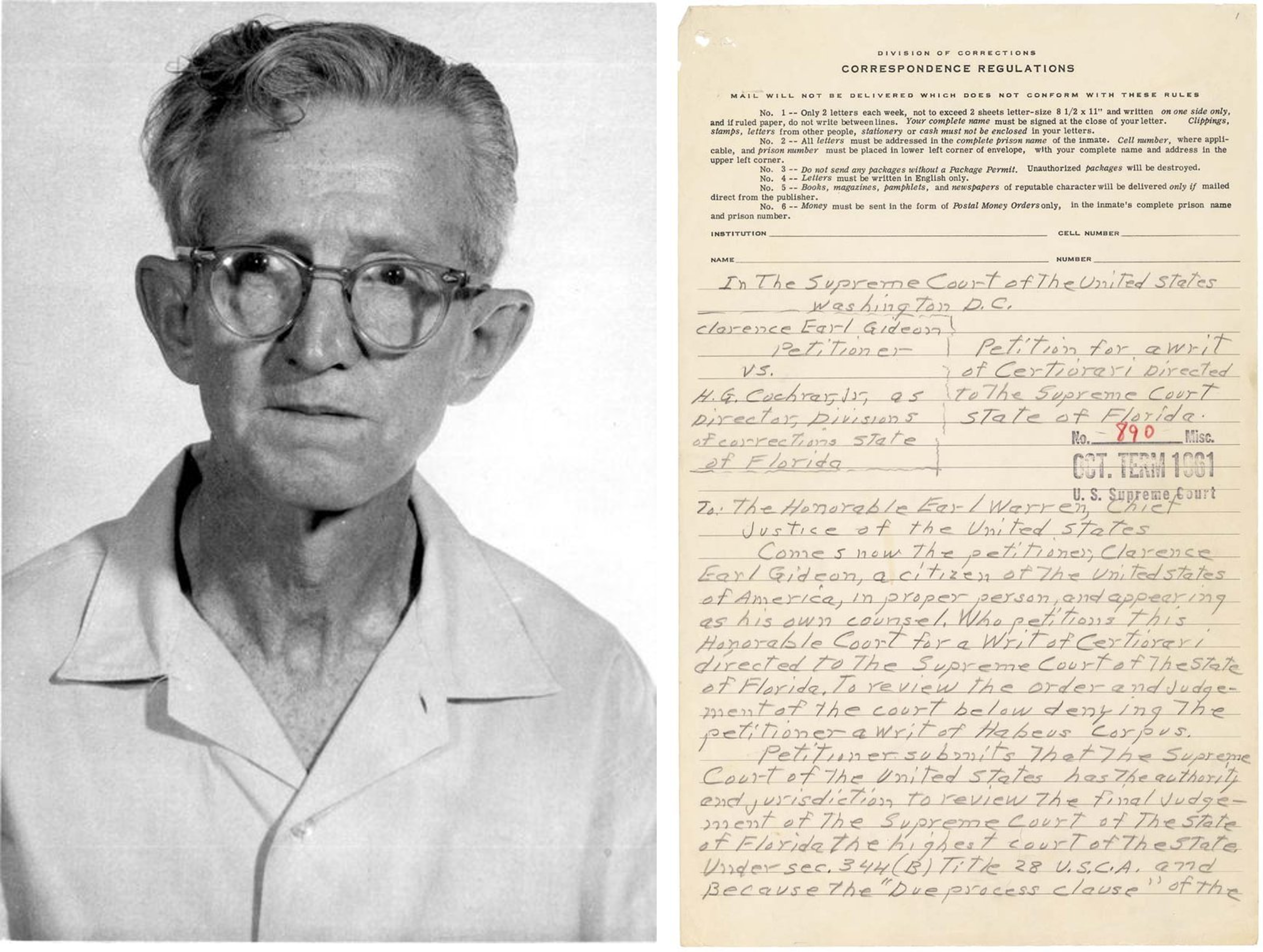

In the landmark case of Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), the U.S. Supreme Court holds that the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of counsel is a fundamental right essential to a fair trial and, as such, applies the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The practical effect of the decision was to require the establishment of public defender organizations in every state to provide free legal counsel to anyone charge with a crime.

However, the Sixth Amendment explicitly applied only to criminal cases. In other legal matters where people face the loss of significant liberty and property interests, they do not have an constitutional right to counsel even to this day.

-

The Office of Equal Opportunity Legal Services Program (since reorganized as the Legal Services Corporation, or LSC) become the first government-funded institution providing noncriminal legal services to indigent populations as a component of Lyndon B. Johnson’s war on poverty.

-

An American Bar Association Commission on Nonlawyer Practice recommended that unauthorized-practice rules be relaxed to permit the licensing of paraprofessionals to promote greater access to justice in indigent communities. The ABA ignored the report.

-

New York State makes 50 hours of pro bono work during law school a condition of admission to the bar.

-

Equal Justice, Inc. is formed to help indigent and marginalized people access a quality lawyer at little or no cost.

Credit to: Gordon, R. W. (2020). Lawyers, the Legal Profession & Access to Justice in the United States: A Brief History. Judicature, 103(3), 34-43. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/lawyers-legal-profession-amp-access-justice/docview/2540561112/se-2

“First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.”

—Martin Niemöller.”